The Reserve Bank of Australia has again paused on raising the official cash rate leaving it unchanged from 4.10 %. In his statement on Tuesday the RBA governor Phillip Lowe stated that he expected Australia’s CPI inflation “will continue to decline, to be around 3.5% by the end of 2024.”

An observation by senior APAC economist Callam Pickering noted that “in the second half of 2022 core CPI rose at an annualised rate of 7.4%” However, “in the first half of 2023 core CPI rose at an annualised rate of 4.3%.” Which suggests that the RBA would not need to change the OCR to return inflation to the 2 – 3 % band.

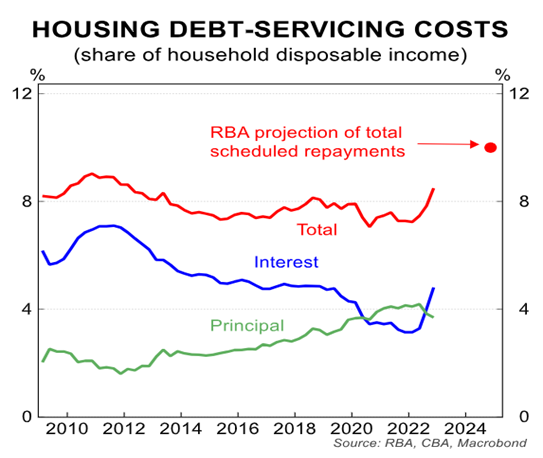

Indeed, this could even be used to justify the RBA beginning to ease the OCR, when we consider the significant monetary tightening factored into Australia with the fixed rate Mortgage cliff. Which will see nearly 500,000 fixed rate borrowers reset from 2% mortgages to 6% mortgages over the second half of 2023 (see graph below).

Anecdotally from conversations with several Real Estate Agents the mortgage rate cliff is leading to a greater number of properties being listed for sale to avoid the interest rate reset.

However, was there another way that could have avoided the pain experienced by a third of Australians facing higher mortgage payments or another third facing unprecedented rental price hikes?

Spain provides an excellent example of an alternative path with their official inflation rate reaching 2%. The key difference lay with the action by the Spanish government, for instance they capped energy prices, lowered the cost of public transport, taxed excess profits, and placed limits on rental rises by landlords. Ultimately, this kept inflation from spreading more widely and consistently across the overall economy. Considering that Australia has a Labor government in power at the federal level, all of these actions could have been introduced.

As it stands the onus remains on the RBA to stabilise Australian inflation, presumably due to the domestic consumer with too much money in their backpocket chasing too few goods. However, most charts reveal a different story namely that consumer and retail sentiment is already subdued or negative, so there might be a different culprit.

One other theory is that one of the leading drivers of higher inflation exists from businesses and people passing inflation costs to others, if and where they can. Essentially, a grown-up version of the childhood game of pass the parcel, a phenomenon that the Bank of England discovered in recent analysis.

The Spanish alternative proposed and adopted something radical in the Australian context, namely that businesses and landlords not only workers needed to take a hit to prevent inflation from running out of control.

It is not too late to change course with the RBA adopting a hold policy on further rate rises and even consider lowering them over the next six months. The government should follow Spain, doing more to hold energy prices down, making businesses play their part, and supporting renters. Spain has demonstrated that that inflation can come down without the economy going into a tailspin.

Australia should do the same.