Australia has found itself within a well publicised cost of life crisis due to rising food, energy and housing costs that are stretching already frayed family and individual budgets. This issue has expanded to such an extent that it now dominates political discourse, influences demographic trends, and challenges the nation’s economic policies and of course is discussed over the family barbeque. Which by all accounts is a key political litmus test.

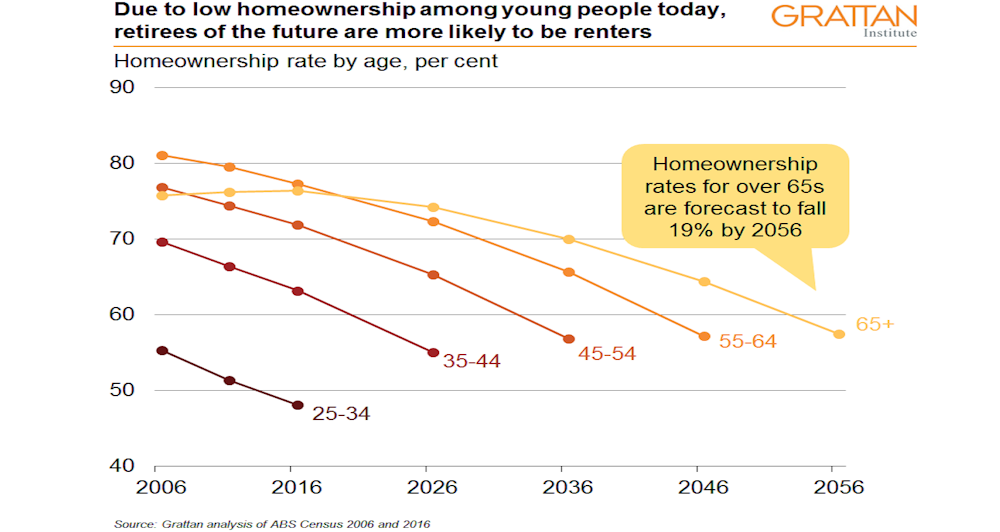

To provide an idea of the scale of the problem in 1981 more than 60 per cent of Australians aged 25-34 had a mortgage; by 2016 it was 45 per cent. The trends are similar among older groups. In the same period, home ownership among the poorest 20 per cent of households has fallen from 63 per cent to 23 per cent. We also explored the need for Australia to embrace a housing strategy in an earlier article.

Amidst this backdrop of economic gloom, the Australian government, under the Labor Party introduced the “Help to Buy” scheme, aimed at mitigating the crisis. The “Help to Buy” scheme represents Labor’s legislative effort to address the housing affordability crisis head-on. It proposes an ambitious plan to assist 40,000 low-income households in co-purchasing homes with the government, which would take a 30% stake—or 40% for newly built homes.

This policy is designed to ease the burden on potential homeowners, making it easier financially for them to step onto the property ladder. Which has been a key component of wealth generation or even a marker of adulthood within Australia. The scheme is a direct response to the growing anxiety among voters, especially young Australians, who fear that their dream of homeownership is slipping away.

The roots of this crisis run deep, exacerbated by soaring housing costs that have led to significant demographic shifts. Sydney is witnessing a startling trend of losing twice as many people aged 30 to 40 as it gains. One of the key reasons for the exodus is the prohibitive cost of housing, threatening the city’s vitality and economic sustainability. Along with the soul crushing commute times to merely go to work, that were the top two reasons that saw me leave Sydney over a decade ago. The NSW Productivity Commissioner issued a stark warning in a recent report suggesting that Sydney could become a city “with no grandchildren,” a pithy quote that summarises the dire consequences of unchecked housing prices on family formation and generational continuity.

One of the impacts of a decline in home ownership will be a greater proportion of retirees that need to rent on a fixed income, which will be challenging. A graph from the Grattan Institute shows this trend below.

Amidst this scenario, the Greens have positioned housing as their frontline issue, championing the cause of renters and those left out of the housing market. They have called for significant reforms, including changes to negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions, along with a demand for a rent freeze. These demands are made in the context of their conditional support for the Help to Buy scheme, signalling a push for a more comprehensive approach to tackling the housing affordability crisis. It certainly seems that this approach is likely to be a vote winner at the next federal election, as the cost-of-living squeeze continues.

However, the Prime Minister has made it clear that there will be no concessions to the Greens’ demands, at least in the immediate term. While refusing to begin negotiation on these policies, the Prime Minister has also kept the door open for future reforms related to housing affordability. This stance reflects the delicate balance the government seeks to maintain between implementing immediate measures and considering broader structural reforms. Particularly, if a change in policy settings impact their primary vote.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the Liberal Party has outlined its response to the housing crisis by proposing a policy that would allow buyers to use up to $50,000 from their superannuation to invest in their first home. Additionally, the party has signalled an intention to lower demand by reducing migration, a move that recognises the reality of a greater number of people competing for a slowly growing pool of homes or rentals. A trend that will continue in the short term due to the cost pressures felt by home builders, that have forced several companies to shut their doors for good. The key difference is that the Liberals are focusing on demand-side measures, which makes sense as we wait for supply side measures to come into effect.

Housing affordability isn’t isolated to Australia but is part of a global challenge that has far-reaching implications. The UK’s Housing Secretary Michael Gove has pointed out, the crisis has the potential to erode faith in democracy and markets. This sentiment reflects a growing disillusionment among younger generations with the economic systems that fail to provide for basic needs such as affordable housing. Gove’s warning identifies the broader societal and political risks posed by the housing crisis, suggesting that it is not merely an economic issue but a fundamental challenge to the stability and legitimacy of our democratic institutions.

Which was once the position of both major parties in the post war years, and that led to Australia having a significantly higher than average percentage of homeowners. It is a relief that both sides of the political divide have recognised that the decreasing rates of home ownership is very much a ‘live’ issue.

The Australian government’s efforts to address the housing affordability crisis, exemplified by the Labor Party’s “Help to Buy” scheme, are crucial steps in a long journey toward ensuring that all citizens can afford a place to call home. However, the Greens and the Liberal Party’s policies show that there are competing ideas on how to address the housing crisis.

As Australia grapples with this issue, it becomes increasingly clear that the housing affordability crisis is more than an economic problem; it is a test of the nation’s commitment to equality, social justice, and the well-being of its citizens. The path forward requires not just innovative policy solutions, but a collective will to ensure that the Australian dream of homeownership remains within reach for all, which would go some way towards restoring faith in our democracy and in the market economy for generations to come.